Presumably the first laboratory task is to learn to make indigo thin films that can function as memristors. To reproduce the results of Nascimento et al., “Low-Cost, Printed Memristor Using Indigo and a Dispersion of Colloidal Graphite Deposited by Spray Coating” [IEEE Electron Device Letters 42, 1468 (2021)], the goal would be a ~100nm thick film of indigo on an aluminum substrate (onto which a carbon-based top electrode would need to be added).

No process details are given in Nascimento et al. so my first step was to search for “spray coater” in the online master catalog of Stanford’s preferred scientific supplies vendors. The one relatively affordable option that seemed plausibly suitable was a bulb sprayer for thin-layer chromatography so I ordered one of those. While contemplating how to set it up to perform the spraying in a reasonably repeatable way, I began to wonder whether it would be possible simply to place small drops on the substrate using a pipetter and let them evaporate — what would be the resulting film thickness?

I set out with the intention of following Nascimento et al. in preparing 10 mg/mL synthetic indigo in ethanol, stirred for an hour at 60C, but I think I actually made 1 mg/mL, as I know I used 100mL ethanol (Gold Shield) and I’m pretty sure I remember weighing out just 0.1 grams of indigo powder (Sigma-Aldrich, as received). First tests with pipetters revealed that 100uL is a hopelessly large drop of liquid for this task. I nevertheless made a test piece by evaporating on aluminum-coated glass coverslips from Platypus.

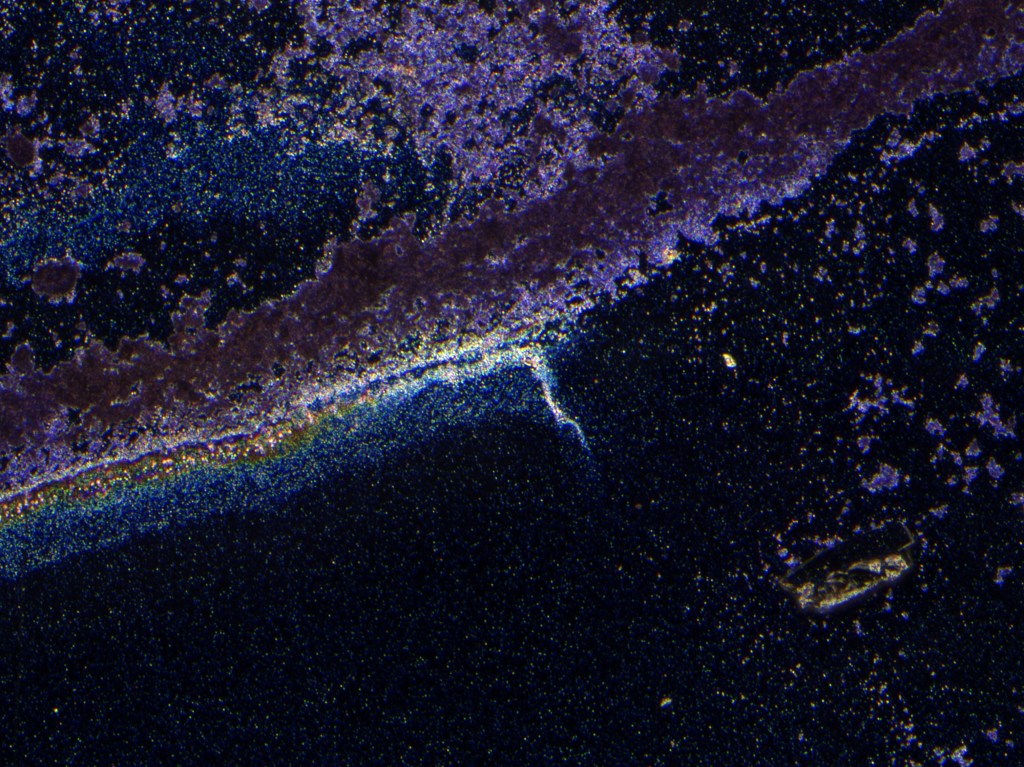

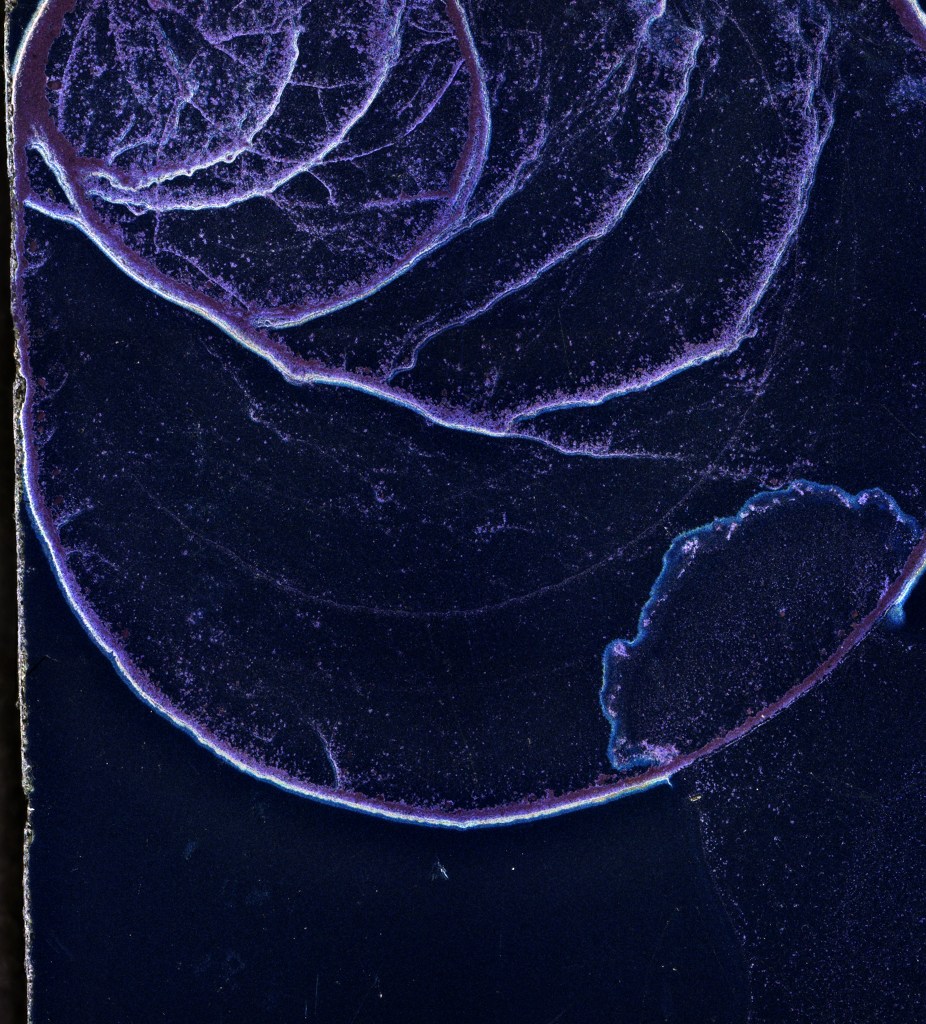

The above image shows a series of rings created by the evaporation of a 100uL droplet of the indigo-ethanol solution (centered on upper-right corner) with the coverslip sitting on a 65C hotplate. Subsequently, another 10uL droplet was placed in the lower right with the coverslip at room temperature.

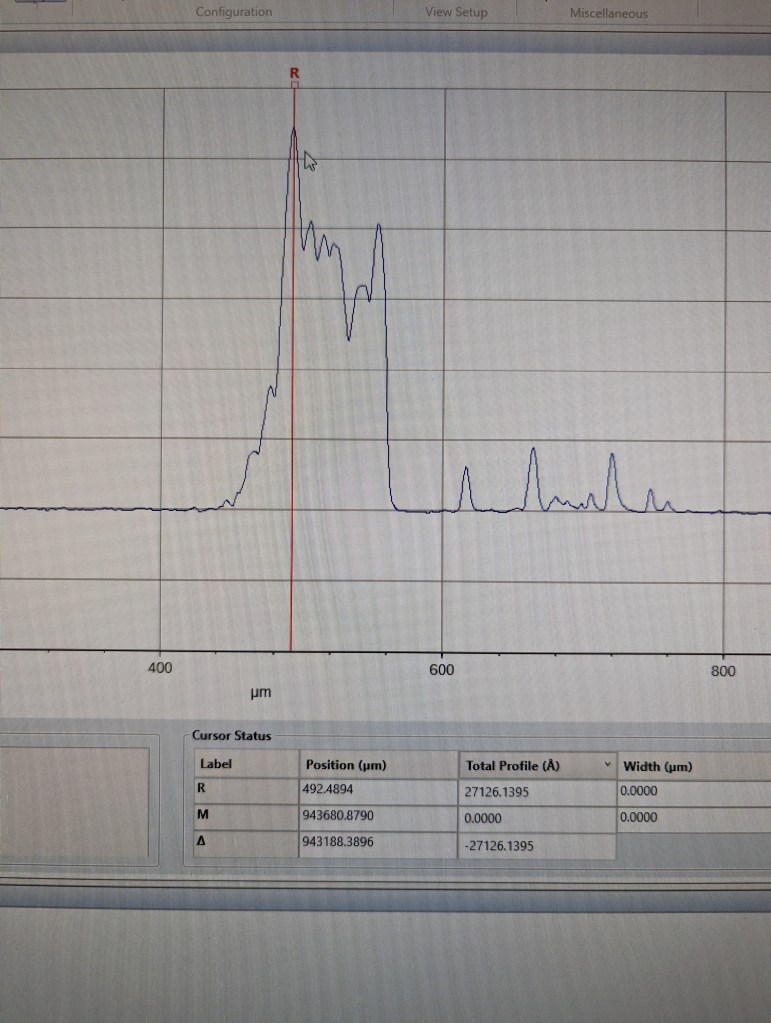

I used the SMF Bruker profilometer to try to get a sense of the thickness of the deposited indigo (a better video showing the data recorded as the tip scans the surface can be found in the blog post for 3 February 2024).

As shown in the following trace, the evaporation ring is really thick — something like 2.7um.

It also seems like the deposition is not really a “film” but rather isolated grains and piles of grains. With these droplet volumes, the footprint ring really seems to gather up most of the indigo. I was reminded of similar issues from my spring semester junior paper (with Aksel Hallin) at Princeton, in which we were trying to avoid similar clumping in the evaporation of a stock solution containing nuclear isotopes on a source foil (the escaping electrons would lose some energy traversing the finite film thickness, thus complicating measurement of the beta-decay spectrum). I remember back then we had the idea to use insulin as a wetting agent to try to minimize beading (equivalently the droplet contact angle). I thought it might be fun to try using the Smartzoom microscope to see if it was possible to take a video of the droplet evaporation and was rewarded with this:

I spent a bit of time wondering whether it should be obvious that smaller droplets would be better. The answer seems to be yes — some scaling relations in this PDF. So the next step would seem to be to figure out a simple way to generate really small droplets, far smaller than what can be done with a pipetter (the above video is with a 1uL droplet).