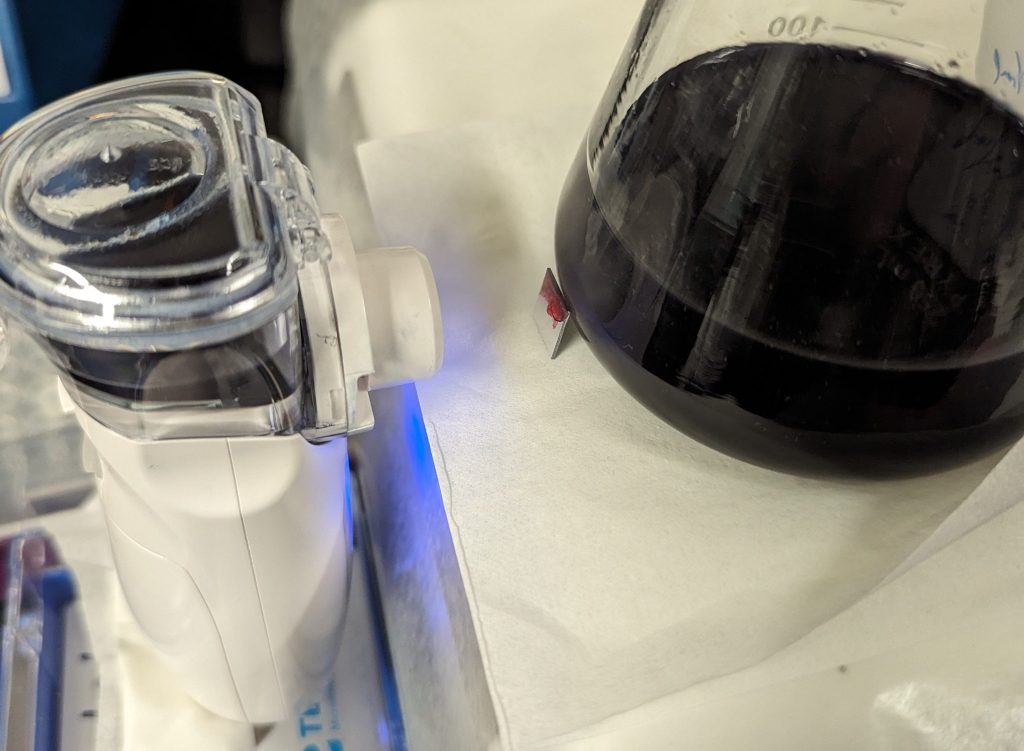

A broader search for simple ways to produce superfine droplets turned up the term “ultrasonic nebulizer,” which eventually led me to a category of small, battery powered, inexpensive health appliances meant for producing fine mists to inhale for respiratory therapies. Various ads claim that this kind of device produces droplet sizes in the range of 4-5um, which sounds great.

In practice the mist produced by such a device is indeed superfine, but this creates a slight difficulty in that the stream of droplets is readily deflected by very slight air currents. For an inhaler device this wouldn’t be a problem but for depositing droplets on a substrate this behavior pushes you to just fire the droplet stream straight at the target from close range.

After a few tentative initial trials that seemed not to be depositing nearly enough indigo on the aluminum-coated glass coverslip, I let the nebulizer fog out a good 4ml of solution in the above configuration. The reddish goo on the upper part of the square substrate is First Contact polymer, which is generally marketed for cleaning optics but I’ve been having good results using it to remove deposited indigo from these substrates so that I can reuse them after failed deposition tests. It is also convenient for masking off parts of the substrate from deposition, as done here.

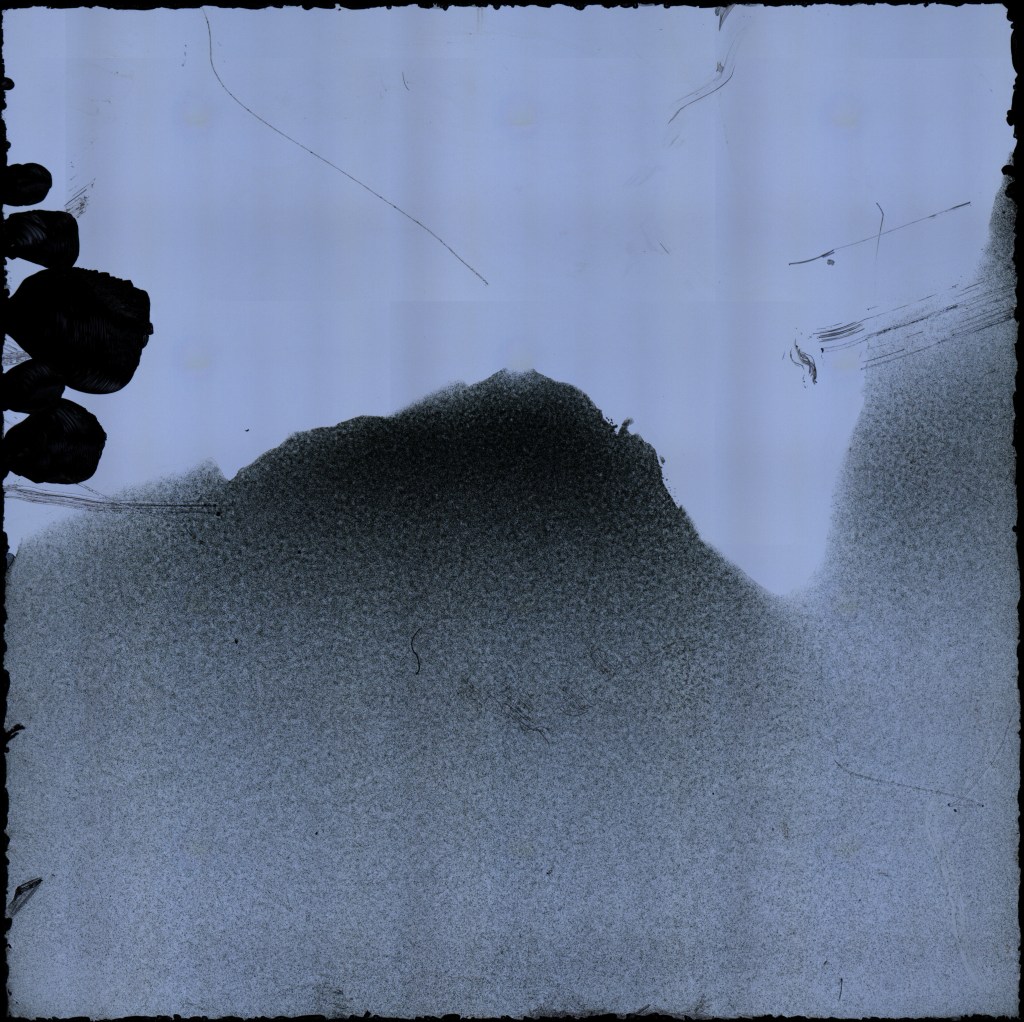

After peeling off the polymer mask, here’s what the substrate looks like at 101x magnification and coaxial illumination (indigo grains appear dark, bare aluminum-coated surface appears light):

There are some conchoidal chips visible near the upper left edge as well as a few scratches from my clumsy handling of the substrate with forceps and hemostat, but generally there’s a clear picture of indigo grains deposited in the lower/right part of the substrate, which was not masked by polymer. The darkest region is roughly center. The following images show close-ups of the edges of darker and lighter areas at 1010x magnification:

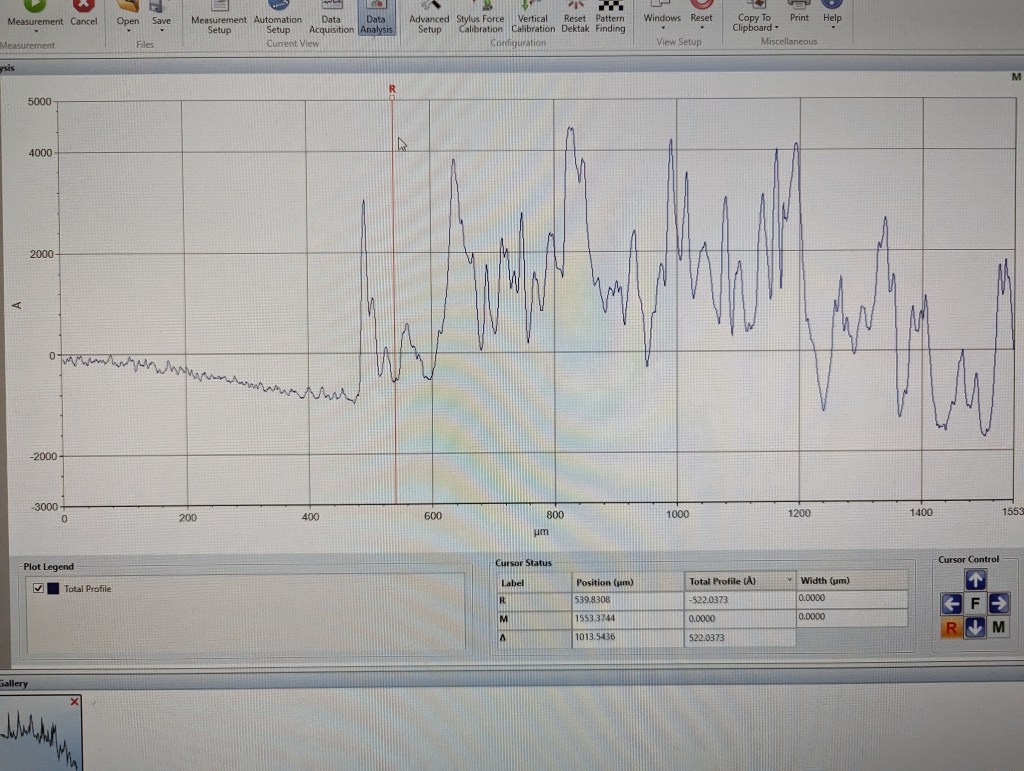

It seems clear from these images that even the dark coated regions are still grainy with some bare spots still visible. I went back to the Bruker profilometer to get a sense of the thickness and thickness variation in the dark region:

The following photo of the profilometer trace suggests that the thickest grains run around 400nm while there may not be as many truly bare spots between them as the microscope images suggest — the valleys between the peaks seem to still be perhaps 40nm above the substrate?

This seems sufficiently promising that I’m starting to think about how to do some electrical tests. A next step could be to prepare some relatively thick depositions, using either the same procedure with a somewhat longer nebulizer runtime (more solution) or perhaps I’ll actually make the 10 mg/mL stock solution and try that. For electrical contacts I’m thinking small dots of some carbon-based conductive glue or other coating on the top, and probes coated in conductive grease — this will hopefully facilitate making decent contact with the rough indigo surface while not stressing the coating in a way that peels it off the aluminum substrate.